Introduction

American warships are already off the coast of Venezuela. Trump speaks of narcotrafficking, but is that really the whole story? Let’s break down what’s behind these maneuvers — and why oil is once again carrying a risk premium.

Why Venezuela?

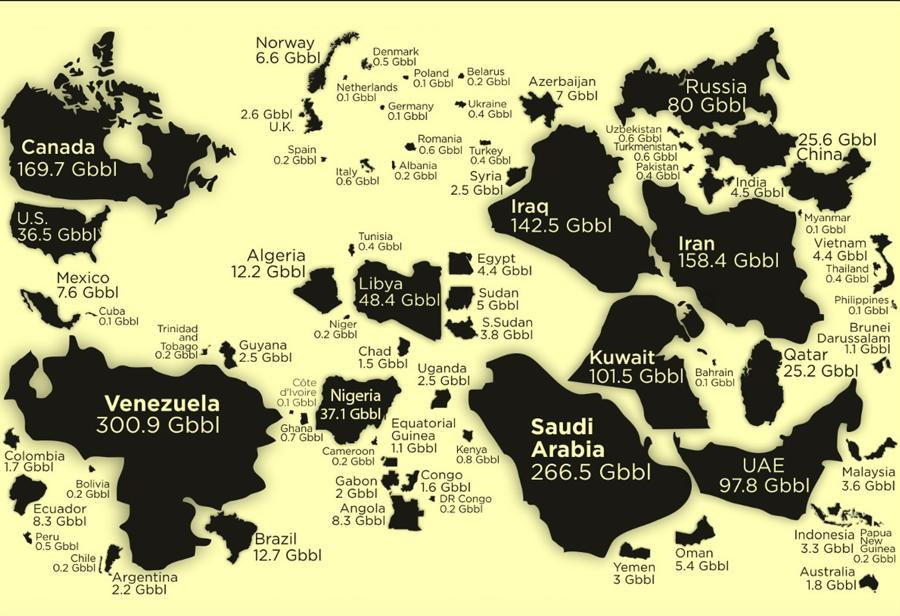

Venezuela holds the world’s largest proven oil reserves — more than 300 billion barrels, surpassing even Saudi Arabia. Yet its state oil company PDVSA has been crippled by years of mismanagement, corruption, and US sanctions, leaving production stuck around 500,000 barrels per day — a fraction of its potential.

Still, Venezuela remains a crucial player for global flows. China has become one of its biggest customers, keeping Maduro’s regime afloat, bypassing sanctions with disguised shipments and barter deals. This connection ties Caracas directly to Beijing’s energy security — and gives Washington one more reason to turn Venezuela into a pressure point.

Rubio and the military escalation

The first strike came from US Secretary of State Marco Rubio. The State Department calls Nicolás Maduro an illegitimate president and the leader of the “Cartel of the Suns,” responsible for narcotrafficking into the US and Europe. In August, Washington raised the bounty for his arrest to $50 million, while the White House openly declared that “any element of American military power” could be used against Caracas.

In response, Maduro announced a mobilization and deployed around 15,000 troops to the Colombian border. At the same time, US warships approached Venezuela’s shores, officially under the banner of a counternarcotics operation. Caracas appealed to the UN and its allies, calling for protection against American aggression.

Exxon vs. Venezuela — a long war

The conflict between Washington and Caracas is not just about narcotrafficking. At its core lies oil. ExxonMobil has been at odds with Venezuela for decades: the nationalization of its assets under Chávez, multi-billion-dollar lawsuits in international courts, and blocked investments.

In 2015, Caracas declared disputed offshore waters as its own, including the Essequibo region claimed by Guyana. Yet it was precisely there that Exxon secured a license from Guyana to develop the giant Stabroek field.

Since then, Exxon has become one of the regime’s primary irritants. Its survey vessels clashed with Venezuelan navy patrols, including a 2018 incident. Every new drilling step triggered Caracas’s protests — right up to its latest statements in 2025 against the launch of new FPSOs. For Exxon, Maduro’s removal would mean not only revenge, but direct access to billions of barrels in disputed waters. Production is already underway under Guyana’s and Washington’s protection, but the case remains under review at the International Court of Justice.

Trump and Exxon — interests align

For Donald Trump, ExxonMobil is not just another oil major. It has long been a political patron of the Republican establishment, pouring millions into campaign coffers and shaping Washington’s energy agenda. Exxon embodies the very idea of “American energy dominance” that Trump turned into a slogan during his first term.

The company’s feud with Venezuela is personal: its assets were seized during Chávez’s nationalizations, it fought billion-dollar battles in arbitration courts, and it has been locked out of the world’s largest oil reserves for over a decade. An ouster of Nicolás Maduro would flip the script. Exxon would gain direct leverage over disputed offshore fields through Guyana’s licenses, while Washington could finally re-anchor Venezuela in the Western energy order — pushing out Chinese buyers who have been propping up Caracas with sanctions-busting deals.

For Trump, aligning with Exxon is more than corporate loyalty. It means rewarding an ally, cutting Beijing off from cheap crude, and proving that American gunboat diplomacy still works when markets are at stake.

How markets react if the situation escalates

For now, Venezuela is only adding a modest risk premium. Brent has been trading with an extra $2–3 a barrel built into prices, reflecting the threat of disruption. That’s manageable.

But the market calculus changes the moment talk of a US special operation turns into action. A full-scale intervention would not just freeze Venezuelan exports — it would destabilize the wider Caribbean basin and raise questions about flows from Guyana, which is ramping up to over 1 million barrels per day by 2027. In that scenario, traders would start pricing in a geopolitical shock: a $10–15 spike in Brent is realistic within days, pushing prices toward the $80 handle.

Brent is tightening into a breakout. The $66 trendline is holding like concrete — as long as it stays intact, the bias is higher. The nearest resistance sits at $70-71. If that level cracks, especially under the headline of a US strike or “special operation,” the market will flip from cautious to outright momentum. In that case, $79–80 is not just a target — it’s the natural magnet. And if fear really spills over, the extension points to $83+.

Europe would feel it in inflation, China in industrial costs, and the US shale patch — along with Exxon — would stand to gain. For markets, the real question is not whether Venezuela matters, but how fast risk turns into price action once the first shot is fired.

Conclusion

Venezuela is no longer just a failing petrostate on the periphery. With US warships on its doorstep, Rubio putting a $50 million price tag on Maduro, and Exxon eyeing a return to the world’s biggest oil reserves, the stakes have shifted. This is no longer about narcotrafficking — it’s about who controls the flow of crude in the Western Hemisphere.

For traders, the setup is simple: the chart is coiled, the politics are explosive, and the first headline that confirms military action could turn a slow market into a $10–15 melt-up. For everyone else — from Brussels to Beijing— it’s another reminder that oil remains the ultimate weapon of geopolitics.